Doig River First Nation History

Doig River First Nation (DRFN) peoples (Tsááʔ çhé ne dane) are descendants of the Dane-zaa peoples who have occupied the Peace River region of British Columbian and Alberta for thousands of years. Archaeological evidence from the Charlie Lake cave site shows that the area was occupied from at least 10,500 years ago by people who were hunting bison and other game.

DRFN oral history describes events and people in the area long before the arrival of European explorers.

Tsááʔ çhé ne dane were one of the most important Dane-zaa groups: they were the original “First People” of the Peace River area. Oral history from First Nations as well as European documents, provide evidence of First Nations’ long-term subsistence on the lands in northeastern BC. Tsááʔ çhé ne dane (or Dane zaa) would hunt, gather, trap, and continue their cultural practices with other Dane-zaa kinship groups. These earliest inhabitants of the region were the ancestors of the Doig River and Blueberry River First Nations, or what was once known as the Fort St. John Beaver Band. Members seasonally traveled across the region to the areas of Montney, Dawson Creek, Grand Prairie, TeePee Creek, Dunvegan, and Clearhills. Today these locations are still considered core areas of DRFN’s Territory.

Traditionally, Tsááʔ çhé ne dane followed the teachings of their Nááchę (Dreamers), who were individuals with the power to gain knowledge and insight into the future through dreaming.

Dreams and visions remain an important facet of the Tsááʔ çhé ne dane culture today, and continue to inform DRFN people about how to maintain balance with one another as well as with the animals and land on which they depend. Many DRFN members continue with traditional sustenance practices through hunting, fishing, and the collection of plants and other resources; however, the seminomadic lifestyle (seasonal round) traditionally practiced has been significantly impacted and altered. Most DRFN members now live in permanent communities.

In 1794, Rocky Mountain Fort was established in our traditional territories, and we began to participate in the fur trade. As a result of the fur trade, European culture slowly started to impact our traditional way of living.

In 1900 we signed Treaty 8 in an effort to preserve our lands and natural resources from outside interests. By 1914, we were allotted reserve land at Gat Tah Kwa’ (Montney), one of our traditional gathering places, but for several decades we continued to travel freely throughout our traditional land.

During World War II, the US Army Corps of Engineers constructed the Alaska Highway across our traditional territory. After the war, the highway allowed an influx of settlers and developers to come into our land, and our lifestyle changed dramatically. We were forced to settle on reserves and to send our children to government schools.

The Department of Indian Affairs agreed to sell our first reserve at Gat Tah Kwa’ (Montney) to the Department of Veteran’s Affairs and we were forced to move further north, to the land on Hanás̱ Saahgéʔ (the Doig River), where our community is centered today.

Land Use by Dane-zaa Peoples

In the late 1700’s, Dane-zaa peoples became active in the fur trade due to the establishment of fur trade posts in northeastern BC by the Northwest Company. By 1828, Hudson’s Bay Company journals report a decline in the Dane-zaa population of the Peace River area due to sickness and death. (Over the next hundred plus years, major epidemics frequently swept through the area, claiming the lives of significant numbers from both white and First Nations communities.) By 1872, the Peace River region was recognized as having huge potential for mining and agriculture. In 1898, the Dane-zaa people opposed gold miners heading north through their territory to the Klondike until the Crown agreed to a Peace Treaty.

The Crown began the process of obtaining signatures from several First Nations within Treaty 8 territory in 1899. A year later, in 1900, government officials returned to the area to obtain signatures on the treaty from the Fort St. John Beaver Band, ancestors of the Doig River and Blueberry River First Nations.

The government of British Columbia enacted the Game Amendment Act in 1905, which threatened the Dane-zaa’s ability to carry out their traditional rights. Further, in 1911, the province imposed a trapline registration system and many Dane-zaa members were unable to pay the fees or were otherwise unprepared to register. As result, many members’ traplines were taken over by settlers.

In 1914, the Fort St. John Beaver Band selected a traditional gathering place in the area now known as Montney for the site of their reserve. By the 1940’s there was substantial interest in developing oil and gas resources in the area and the Band surrendered the mineral rights associated with its Montney reserve to the Crown in trust, to lease, for its benefit.

In 1927, due to changes to the Indian Act, First Nations were legally barred from raising money to address lands claims concerns. This was followed by further changes to the Act, making it a criminal offence for First Nations to hire lawyers to assist them with land claims settlements. This amendment was finally repealed in 1951.

After WWII ended in 1944, Canada’s Department of Indian Affairs sought the Montney reserve lands for settlement by returning soldiers due to its high agricultural potential. As a result, the Fort St. John Beaver Band surrendered the reserve lands to the Crown. In return, they received three small reserves close to their trapping areas at the Doig, Blueberry and Beatton Rivers, totaling 6.194 acres, approximately one third the size of the Montney Reserve.

As settlers immigrated to the area, taking up farming as well as industrial development, it became difficult to maintain the semi-nomadic lifestyle the First Nations traditionally practiced. The reserves at Blueberry River and Doig River became permanent, year-round settlements. By 1977, the Fort St. John Beaver Band split into two separate communities, the Doig River and Blueberry River First Nations.

Over the coming decades, the oil and gas industry boomed in northeastern BC, including on the lands surrendered by the First Nations at their former Montney Reserve.

The Nations were not seeing the benefits of the royalties which were to flow from the federal governments ‘in-trust’ status of those lands and in 1978, Blueberry River and Doig River First Nations commence a suit against the Department of Indian Affairs over the lost revenues. It took seventeen years before the case was resolved and won by the Nations. In 1995, the Supreme Court of Canada found the Crown had breached its fiduciary obligation by selling the Nations’ mineral rights on the former reserve. The bands and the Crown reached an out-of-court settlement as restitution for the lost royalties. Doig River First Nation established a trust fund with their settlement funds.

The WAC Bennett Dam, near Hudson’s Hope and within DRFN’s traditional territory was completed in 1968. Construction of the dam resulted in the flooding of 350,000 acres of forested land, drowning countless animals and blocking mountain caribou migration routes.

By 2003, the Chiefs of seven Treaty 8 Nations (including DRFN) requested that the province of BC develop a coordinated action plan with them to exercise Title and Rights on the lands of their collective Treaty 8 territory. Five years later, in 2008, DRFN signed an Economic Benefit Agreement (EBA) and a series of Collaborative Management Agreements (CMA’s) focused on resource revenue sharing and land management. The overarching purpose of the agreements was to “…affirm a new and ongoing relationship on the basis of mutual respect and understanding”.

Five years later, DRFN took action to address additional resource development issues that significantly impacted their people and lands. In 2008, they filed a mineral rights claim in response to Canada’s breach of its fiduciary obligation associated with failing to reserve sub-surface mineral rights when purchasing the Nation’s new reserves. A registered BC trapline claim was also filed in 2008, to account for the failure of the federal government to protect traplines when the BC Trapline Registration Process was initiated and implemented in 1926.

In 2010, DRFN signed an MOU with the City of Fort St. John, establishing a framework for working together to establish and urban reserve in or near the City. Since that time, DRFN has conducted consultation with its membership and has worked to develop plans for some of the lands they anticipate acquiring in the very near future. The community is excited to initiate economic development initiatives within the City and make positive contributions to the business and service needs of both its members and residents of the City.

Another exciting and progressive initiative of DRFN was confirmed in 2011 with the official establishment of its K’ih tsaa?dze Tribal Park (KTP). The park consists of 90,000 hectares of land just northeast of the reserve and is an important area that will be managed by the band for the benefit of the community.

In 2014, the province of BC announced its intention to proceed with the development of the Site C dam, another massive industrial project that would significantly impact over 107 km of river valley and 57,000 acres of agricultural and forested land in the southern portion of DRFN’s territory. Despite participating in the review proceedings as well as court challenges to defend the territory, the project is underway.

By 2015, DRFN withdrew from its EBA and CMA’s because they felt that British Columbia failed to implement the agreements, thus not providing the protection required to ensure community members could adequately practice treaty rights. These agreements have yet to be renegotiated, however plans are underway to address this matter.

One of the latest court rulings to affect DRFN occurred in 2017, where the BC Supreme Court made a ruling on the western boundary of Treaty 8. The court found that the boundary should extend to the height of land along the continental divide between the Arctic and Pacific watershed. As a result, treaty land entitlement (TLE) claims by DRFN and other area bands is presently on-going and are anticipated to be finalized in the near future.

In addition to their intention to renegotiate its EBA and CMA’s, DRFN is actively engaged in initiatives that will advance control and management of their lands. Treaty Land Entitlement as well as Tripartite Land Agreements negotiations are underway. There are plans to renegotiate economic and collaborative management agreements. Further, steps are being taken to negotiate government to government as well as Alberta consultation agreements.

See our historical timeline here.

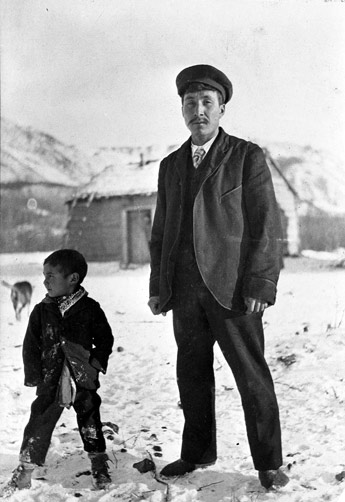

Who was Chief Montney?

Montney Creek runs through Gat Tah Kwą̂. This creek, and the agricultural community now located here, were named after our Chief Montney. He died here in 1918, at the age of seventy-two, during the Spanish flu epidemic that ravaged our people.

Gat Tah Kwą̂ lies just north of the city of Fort St. John. The name means “Spruce Among House,” which refers to the large number of teepees our people had here both before and after Europeans came to our land. Our dancing grounds at Gat Tah Kwą̂ are called Suunéch’ii Kéch’iige, which means “The Place Where Happiness Dwells.”

Elders such as May Apsassin, Tommy Attachie and Madeline Davis, remember how our people would gather there every summer to court, celebrate births, settle political issues, visit with relatives, and to drum, sing, and dance.

The Dreamer Gaayęą named one of his songs “Suunéch’ii Kéch’iige.” When our songkeepers sing that song now, it reminds us of the importance of the Dreamers’ Dances we held there. Gaayęą died at Gat Tah Kwą̂ in 1923 after falling off of a horse, and we continue to care for his grave here and follow his teachings.

Who was Chief Succona?

Chief Succona was the half brother of the Dreamer Oker. He is was born in 1879 and died on June 24, 1952. He was the father of George Succona and Madeline Succona Davis, and the grandfather of Margaret Dominic Davis and Chief Kelvin Davis. Succona became Chief after the death of Chief Montney in the 1918 flu.

Historical Resources

Historical Resources by Anthropologist Robin Ridington and Jillian Ridington who have been working with the Beaver Indians since the 1960’s:

- Where Happiness Dwells: A History of the Dane-zaa First Nations (2013)

- When You Sing It Now, Just Like New: First Nations Poetics, Voices and Representations (2006)

- Trail to Heaven: Knowledge and Narrative In A Northern Native Community (1992)

- Little Bit Know Something: Stories in a language of anthropology (1990)

- Dane Wajich: Dane-zaa Stories & Songs – Dreamers and the Land, Virtual Museum of Canada

- Doig River First Nation, Government of British Columbia

- Investing with Doig River First Nation, Trade and Invest BC

- A Gallop through our Peace Region History

Selected Bibliography about Dane-zaa Culture

Brody, Hugh. 1981. Maps and Dreams. Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre.

Burley, David, Scott Hamilton and Knut Fladmark. 1996. Prophecy of the Swan: Fur Trade History of the Upper Peace River Valley, 1794-1823. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Goddard, Pliny Earle. 1916. “The Beaver Indians.” Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. 10.4.

Ridington, Robin. 1988. Trail to Heaven. Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre

Roe, Steve and Students of Northern Lights College. 2003. “‘If the Story Could be Heard’: Colonial Discourse and the Surrender of Indian Reserve 172.” BC Studies. 138/139: 115-135.

Archaeology

Archaeological studies at Charlie Lake Cave, located just west of Gat Tah Kwa’ (Montney), show that Aboriginal people inhabited our lands in northeastern British Columbia more than 10,000 years ago. The history of our people reaches back into this “long ago” archaeological era. Our history is also documented in the early historic period when explorers and fur traders came to our land and relied on us to trap and hunt for them.

Charlie Lake Cave Excavations

http://www.sfu.museum/journey/an-en/postsecondaire-postsecondary/grotte_du_lac_charlie-charlie_lake_cave